The Hidden Abuse

Diocese kept abuse cases secret

By Steven Church

The [Wilmington DE] News Journal

11/20/2005

http://www.delawareonline.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=

/20051120/NEWS/511200333/0/NEWS01&theme=PRIESTABUSE

[See links to other

articles, documents, and transcripts of interviews in this series,

including a major article

on alleged abuse by Rev. Edward D. Carley. See below for parishes

and schools where accused priests worked.]

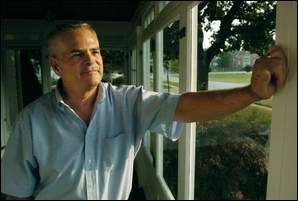

Michael Schulte remembers being in the family bomb shelter at the height

of the Cold War when he told his parish priest about being raped as a

middle school student.

Father Douglas W. Dempster had come to Schulte's New Castle County home in the Milltown development of Sherwood Park to investigate the teenager's claim that a Roman Catholic priest had sodomized him during overnight trips to Philadelphia and Virginia.

|

| Michael Schulte told church officials in the early 1960s that he was sodomized by a diocesan priest. A colleague of the accused investigated for the church but never informed law enforcement. The News Journal / William Bretzger. |

Schulte had kept the sexual assault secret for two years, until the day

he saw his attacker get out of a car with a young boy from his neighborhood.

When Schulte finally came forward, church officials didn't call police

or hire a counselor for him. It was the early 1960s, and those tactics

would not become standard until 2002 -- when the abuse scandal in Boston

became national news.

Instead, they sent Dempster, who, according to Schulte and his mother,

questioned the boy alone in a soundproof, underground vault. Today, despite

reforms adopted under the glare of press scrutiny, Schulte is still waiting

for the results of Dempster's inquiry.

Interviewing a child in private, without his parents, was just one tactic Catholic leaders in Delaware used that buried allegations of child molestation, a News Journal investigation of clergy sex abuse in the Diocese of Wilmington shows.

The News Journal examination is the first public attempt to chronicle how church leaders in Delaware handled molestation claims. Neither the church nor Delaware prosecutors have ever published a full account of abuse in the diocese, where at least 30 priests have been accused of molesting more than 60 children since 1950.

The review showed that in many ways, the Diocese of Wilmington mirrored the Archdiocese of Philadelphia, where church officials knowingly bounced abusive priests from parish to parish, according to a three-year grand jury investigation recently released in that city.

Church officials in Delaware negotiated secret legal settlements with victims, sent accused priests to therapy instead of reporting them to police and moved suspected abusers to other states, according to victims, church officials and court documents.

But the Diocese of Wilmington -- which includes all of Delaware and the Eastern Shore of Maryland -- also faced a shortage of priests.

To meet the spiritual needs of a growing Catholic population, bishops here had a policy of accepting problem priests. In 1978, for example, the church ordained a deacon named Edward Francis Dudzinski Jr. to the priesthood despite allegations that the young man had inappropriate contact with a handful of middle school boys in Easton, Md.

Seven years after becoming a priest, Dudzinski was removed from active ministry when he was accused of molestation.

At least half of the 57 parishes in the diocese -- and four of its seven Catholic high schools -- have had an alleged molester on staff. That number is based on just 11 accused priests whose names have surfaced in lawsuits or whose identities were reluctantly released by church officials.

The names of 23 accused priests have been closely guarded by the church, even though Catholic officials have concluded the men had "credible allegations" of abuse made against them. The church will not define what "credible allegations" means. Keeping those names secret has prevented the full extent of the molestation scandal from becoming public.

|

| In 2002, Bishop Michael A. Saltarelli pledged to implement the "Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People" that was written by the U.S. Conference of Bishops. |

Bishop Michael A. Saltarelli and the other top-ranking church officials have declined to provide details about the actions of the accused priests.

Victims demand names

Victims have long wanted church officials to release the names and assignments of all the priests with credible allegations of abuse made against them. That way more Catholics would know whether an accused priest ever worked or lived at their home parish.

Church officials in Delaware, like at the other 194 dioceses nationwide, say they are focused on the future and promise to do a better job of handling new sex abuse allegations.

"The people in our diocese can look and see what we have in place to protect children," diocese spokesman Robert G. Krebs said. "They can look and see the programs in place to help victims. And they can know that we did release the names to the authorities. I have not heard, and no one in the diocese has heard, a good argument for releasing those names to the public."

The church argues that releasing internal documents could be unfair to the accused priests, nearly all of whom have never been convicted of a crime. And many victims don't want the priest who abused them to be publicly named, Krebs said.

|

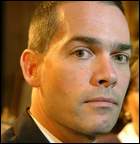

| Lt. Cmdr. Kenneth J. Whitwell said he was sexually abused by the Rev. Edward Smith throughout his high school years at Archmere Academy. |

However, details continue to leak. On Thursday, a U.S. Navy officer sued Archmere Academy in Claymont and the Wilmington Diocese in U.S. District Court in Wilmington, claiming that he was sexually abused by a priest while he was an Archmere student. The lawsuit claims that Catholic officials sent the Rev. Edward Smith to Archmere in 1982, even though Smith had been removed from a Philadelphia high school for sexual misconduct two years earlier. [See Whitwell's lawsuit.]

Lt. Cmdr. Kenneth J. Whitwell, 37, of Quantico, Va., said he was sexually abused by Smith throughout his high school years, beginning when he was a freshman.

"I was a shy 14-year-old," Whitwell said. "He basically carved me out of the pack."

Agreed to charter

In 2002, Bishop Saltarelli pledged to implement the "Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People" that was written by the U.S. Conference of Bishops and approved by the Vatican in response to the abuse scandal.

The charter calls for bishops to renounce confidential legal settlements, pledge to always inform police whenever they become aware of an allegation and to offer counseling to anyone who comes forward claiming to be a victim. The bishops also adopted a zero-tolerance policy that required them to remove any priest from active ministry if a "credible allegation" of abuse is made against him.

Those reforms, however, came too late for more than 60 victims in the Wilmington diocese that church leaders identified over the years.

Surprised by priest's language

When he entered the concrete-lined chamber, Schulte recalled, he assumed the rebellious stance of an angry teenager, leaning against a post with his arms crossed as he waited for Dempster to say something. Dempster was a close associate of the priest the teenager accused of sexual abuse.

Schulte said he was stunned when Dempster, in his late 20s at the time, used foul language warning him not to repeat his claims to anyone. [See a partial transcript of the Schulte interview, with a link to a streaming video.]

"He wanted to know, 'How f'ing far is this going to go?'" recalled Schulte, who is 57.

Dempster, who is retired and lives in Marydel, Md., denied that he cursed at Schulte.

"I would never use those words, no," said the 68-year-old priest. He met with the family about Schulte's accusations, but does not remember going into the bomb shelter alone with the boy, Dempster said in an interview at his home.

On a previous trip to the house, he had visited the bomb shelter, Dempster said, but was uncomfortable with the closed-in feeling of the underground space. For that reason, he said, he doubted he would have taken Schulte there to speak.

Dempster said he never reported Schulte's accusation to the police because that was not his role in speaking to the family.

"My only job was to contact the authorities -- church authorities," Dempster said.

Diocesan officials in Wilmington eventually sent the accused priest to a hospital, Dempster said. He said he does not know what kind of treatment the priest may have received. A Catholic Directory from that time listed the priest as "on sick leave."

"I know they handled it and did their best with it," Dempster said.

Dempster said he never formed his own conclusion about whether the priest was guilty of raping Schulte.

The priest went on to serve in several other parishes in the diocese before retiring in the early 1990s.

Diocese spokesman Krebs declined to comment on Schulte's claims.

Schulte's parents, Doris and John Schulte, waited outside the bomb shelter door, trusting Dempster's word that he needed to speak with their son alone, said Doris Schulte, who is 84 and lives in Pennsylvania. Afterward, Dempster talked with them, she said.

"He said that, 'It is absolutely forbidden that you ever repeat what you have heard,'" Doris Schulte recalled, quoting Dempster.

Dempster said he does not remember all of the details of his meeting with the Schultes. He said it is unlikely that he would have instructed them not to speak about the allegations.

"I don't remember that," Dempster said. "It's so many years ago."

Similar experiences

The Schultes' story reflects the experience of thousands of families across the country, experts say, especially those who were victimized in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s.

"The consistent theme throughout those decades was that there was never any mention of law enforcement," said David Clohessy, national director of Chicago-based SNAP, Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests. "Victims were never told this was a crime. The emphasis was very heavy on secrecy."

Doris Schulte and her husband, who is deceased, were regular members of St. John the Beloved in Sherwood Park, where the family lived. They taught their eight children to respect the word of a priest and to volunteer at the church, where their sons were altar boys.

Like the overwhelming majority of victims, Michael kept the molestation secret for years. In 2004, a study commissioned by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops found that only 13 percent of victims came forward in the same year that they were molested by a priest.

Joe Schulte, Michael's oldest brother, was the first person Michael tried to tell about being raped.

"I was completely shocked. I walked away a little bit," Joe Schulte said. "And then I came back and said, 'You cannot tell anybody this. Forget it happened. Don't tell anybody about this.' "

After that, Michael, who was 14 or 15 at the time, told his mother and father about the sexual assault. His father went to see the bishop at the time, the Rev. Michael W. Hyle, who insisted that the family allow church officials to handle the priest themselves, Doris Schulte said.

The family never reported the incident to the police and never considered suing the priest.

"We went through the channel that was acceptable at that time," she said.

But from that point forward, the family's Catholic faith was shattered. Doris Schulte became a Presbyterian. Her husband lost his faith entirely, becoming bitter about a $100 contribution he had made to the church, Joe Schulte said.

"I knew my father was upset," he said. "He was especially angry about that period of time."

Because of the way the church handled the incident, the family didn't speak about Michael Schulte's allegations again for decades.

Screening new priests

Since at least the 1950s, the Diocese of Wilmington has struggled with a shortage of priests, said Monsignor Paul J. Taggart, who served from 1966 to 1995 as vicar general of the diocese, considered second-in-command after the bishop. Taggart died earlier this month after a lengthy illness.

During his time, Taggart said in an interview in 2002, the diocese never knowingly accepted a priest who had sexually abused a child. But the diocese would accept just about any priest who was able to perform his duties, as long as he was not in serious trouble, Taggart said.

"I think we were more open than other dioceses in taking priests who needed a second chance," Taggart said.

Since 1950, three priests from other dioceses who were ministering in the Diocese of Wilmington have been accused of sexual molestation, according to a letter Bishop Saltarelli wrote to Catholics in Delaware in January 2004.

When a priest from another diocese was discovered to have abused a child, "we would show the door to the person," Taggart said.

Under church rules, a priest must get permission from the local bishop before he can minister in a diocese, even if that priest is part of an autonomous religious order that does not report to the bishop.

In 1971, Wilmington diocese officials considered accepting a priest who had been accused of sexually molesting teenage boys in the Diocese of Worcester, Mass. The priest was rejected, however, because of a negative evaluation by his psychiatrist, according to court documents filed in 1994 as part of a lawsuit against church officials in Worcester. [See Worcester bishop Flanagan's request and Wilmington bishop Mardaga's reply.]

Had the doctor given David A. Holley a positive report, he might have been accepted by the bishop of Wilmington at the time, the Rev. Thomas J. Mardaga, according to the documents.

"Regrettably, Father Holley's case presented a greater problem than we could handle, at least with the present prognosis," Mardaga wrote to the bishop of Worcester.

Holley was eventually sent to New Mexico, where he was convicted of molesting several boys and sent to prison.

Six years after Mardaga rejected Holley, he elevated Dudzinski into the priesthood -- despite concerns about Dudzinski's relationships with junior high school-age boys in the Saints Peter and Paul Parish in Easton. Dudzinski was working as an intern priest at the time.

Several months before he became a priest, Dudzinski was forced to attend psychological counseling when his superiors in the parish discovered that he had taken one boy on an overnight fishing trip and had pressured another boy's mother to let him take her eighth-grade son on vacation with him. When the woman refused, Dudzinski asked another boy instead, according to an internal church memorandum that later surfaced in a 1989 sexual abuse lawsuit against the church.

Two women confided to Father Edward M. Aigner Jr., who was supervising Dudzinski in Easton, that they were uncomfortable with the amount of time Dudzinski had been spending around their middle school-age sons. Aigner outlined the women's discomfort and his own concerns in a June 22, 1977, memorandum to diocese officials. In the end, Aigner took the unusual step of refusing to either endorse or oppose Dudzinski's application to the priesthood. [See the 1977 memo on Dudzinski.]

In 1985, 15-year-old Barry Lamb of Brandywine Hundred accused Dudzinski of sexually abusing him during summer trips to the Busch Gardens amusement park near Williamsburg, Va.

When Lamb told his parents in August 1985, he didn't give them all of the details immediately, said his father, Nelson Lamb.

"We didn't know how horrendous it was until years later," Nelson Lamb said.

For that reason, and because Nelson Lamb was an extremely devout Catholic, the family reported the incident to the church -- not the police.

Two priests, one of whom was a high-ranking diocese administrator, met with the family and, afterward, alone with Barry. The diocese official persuaded Nelson Lamb to send Barry to counseling at Catholic Social Services and convinced him that the church would take responsibility for Dudzinski.

Diocese officials have acknowledged that Dudzinski is on their list of priests with credible allegations of abuse made against them and have said that the church paid Barry Lamb to settle the 1989 lawsuit he filed. Krebs declined to answer questions about Lamb's case. [See a court filing by Rev. Dudzinski and Bishop Mulvee in this case, advancing several reasons why they are not liable for the abuse of Lamb.]

Barry Lamb said the priests made him feel guilty about reporting Dudzinski. "The specific question they asked me was, 'What did I do to make him do that to me?' " Barry Lamb said.

At no time did church officials suggest that the family report Dudzinski to the police, the Lambs insisted. And Nelson Lamb said he regrets not taking his son to the police immediately.

Years later, when Barry Lamb was in college, he tried to have Dudzinski arrested, but by then the statute of limitations had expired.

Retired Delaware Deputy Attorney General Keith Trostle said prosecutors tried unsuccessfully to find a way to file criminal charges on Barry Lamb's behalf. Lamb's case eventually helped inspire prosecutors to push for a change in the statute of limitations, Trostle said. In 1992 Delaware lawmakers rewrote the law, removing a five-year limit that had prevented criminal prosecutions in which victims kept their abuse secret for years.

The 'gentlemen's agreement'

Only one of the 11 priests who have been publicly accused of sexual molestation has been prosecuted, and that involved a police agency outside of Delaware.

In Delaware, the diocese appeared to have a "gentlemen's agreement" with prosecutors about priests who got into trouble with the police, said the Rev. Thomas J. Peterman, an unofficial historian for the diocese who wrote a book that listed the priests who have served in Delaware since the diocese was founded in 1868.

From the 1950s through the 1970s, Peterman said, it was understood by diocese priests that colleagues who were accused of sexual abuse were not investigated by police in Delaware. Instead, they would be sent to places like St. Luke Institute in Silver Spring, Md., for psychological treatment. Afterward, the priest would not be allowed to return to Delaware, Peterman said. Instead, he would be assigned to a parish on Maryland's Eastern Shore.

Peterman said he could recall at least one priest working in New Castle County who was reassigned under that "gentlemen's agreement." He declined to name the priest.

Taggart, the retired vicar general for the diocese, denied that such an unwritten bargain existed, as did former prosecutors in Delaware who served in the 1970s and 1980s.

However, former Attorney General Charles M. Oberly III said that it is possible such an unusual arrangement could have affected how such molestation cases were handled in the 1950s and the 1960s, when the office was still small and child sexual abuse claims were rare -- especially those made against the clergy.

"In the 1950s and 1960s things were totally different," said Oberly, who was Delaware's top prosecutor from 1982 until 1994. "Is it possible a case could be swept under the rug? Certainly."

Few knew of incidents

When church officials took action against a priest accused of molestation, they rarely informed the public, or even other priests in the diocese.

Father Aigner, who cautioned his superiors about ordaining Dudzinski, told the newspaper that on rare occasions, a priest would be reassigned without any warning or explanation from the diocese. Priests rarely stay at one church for more than a few years, so there is nothing strange about getting a new assignment. But usually there are public announcements about personnel changes.

Dudzinski and another priest, Joseph McGovern, seemed to vanish overnight, Aigner said.

"They seemed like they disappeared," Aigner said. "They just weren't around anymore and there just was never a lot of information about them. But you hear things."

Years later, Aigner learned that Dudzinski was sent to a psychiatric institute and then went on to work in another state.

Dudzinski eventually became a counselor in Virginia for teenagers with drug and alcohol problems until new allegations surfaced. He gave up his counseling license in 2003 while he was being investigated by the Virginia Board of Counseling, according to Virginia records. Among the allegations Dudzinski faced was that he slept in the same bed with a minor he was supposed to be counseling.

The fate of McGovern remained a mystery to Aigner until McGovern's name came up in the grand jury report on priest abuse issued by Philadelphia District Attorney Lynne Abraham. The report said that after abuse allegations surfaced against him in 1986, McGovern was treated for pedophilia at St. Luke Institute in Silver Spring, Md., and placed on Depo-Provera, a sexual inhibitor.

In 1987, McGovern was allowed to live at a rectory in the Archdiocese of Philadelphia while he studied at Temple University. But when archdiocese officials learned he was celebrating Mass at Holy Angels Church between 1987 and 1990, they ordered him to find his own residence.

Today, the Diocese of Wilmington continues to pay McGovern a stipend, although Krebs, the diocese spokesman, said he does not know where McGovern is living or what he is doing.

Seeking closure

All of the anger that Michael Schulte had suppressed for years came back one day around the year 2000 when he talked to a childhood friend who also claimed to have been molested by a Catholic priest.

Neither priest has ever been accused of abuse in a Delaware court and the diocese has declined to say whether it has ever received a "credible allegation" of abuse against either man. For that reason, their names are being withheld by The News Journal. One priest did not return phone calls seeking comment and the other declined to talk about the allegations.

Sometime after 2000, Schulte met with Monsignor Clement P. Lemon, the vicar for priests, who works as an advocate on behalf of priests with Bishop Saltarelli. Since 1987, Lemon also has been responsible for investigating priest abuse cases, meeting with victims and interviewing priests.

Lemon remembers meeting with Schulte, but could not recall any details of the conversation, including whether he ever gave Schulte any information about Dempster's investigation.

Schulte said he came away disappointed from the meeting. Lemon was sympathetic, listening carefully to everything Schulte said. But in the end, Schulte only learned that the priest was in retirement in another state.

Victim advocates say that church investigators are much more gentle today than in past decades. One thing remains unchanged, however, said Clohessy, who is with the survivors network: Church officials avoid releasing any details from their internal investigations. Clohessy said that theme remains consistent with the estimated 1,500 victims he has interviewed during his time with SNAP.

The church did agree to pay for Schulte to see a counselor.

During one counseling session at the Catholic Social Services building in Wilmington, Schulte said, he was asked what he would do if he discovered that his abuser was still hurting children and no one was able to do anything about it.

"I told him I'd pop a cap in him myself," Schulte said.

Within days, a Wilmington police detective left several phone messages for Schulte about the threat, but apparently dropped the matter when Schulte didn't call him back, Schulte said.

The counselor had warned Schulte that he would have to report the threat to the police.

After he got the phone messages from police, Schulte said, he refused to go back to counseling.

Although a detective called him regarding the threat he made against a priest, Schulte said, he never got a call from any police agency investigating the priest who abused him.

Contact Steven Church at 324-2786 or schurch@delawareonline.com.

Abuse in the Diocese of Wilmington

The Catholic Diocese of Wilmington has acknowledged that 30 priests who have worked within its borders have had credible allegations of abuse leveled against them, but has declined to name them all. This graphic contains a list of 11 priests who have been accused publicly of molesting children in the past. Seven of these men are on the diocese's list; the other four were identified using court and church records as well as interviews with alleged victims. Only one of the 11, Robert J. Hermley, has ever been convicted of sexually abusing a child. No court has ruled against the other 10.

Lines placed in bold type indicate the assignment and posting of the accused priest, if known, at the time he allegedly abused a child.

[ Carley | Dudzinski

| Hermley | Irwin

| Lind | Mackiewicz

| McGovern | O'Neill

| Rogers | Smith

| Wiggins ]

Ordained 1948, died 1998

1948: St. Mary Refuge of Sinners, Cambridge, Md.

1954: St. Ann's Church, Wilmington.

1962: St. Paul's Church, Wilmington.

1964: Cathedral of St. Peter, Wilmington.

1967: Good Shepherd Church, Perryville, Md.

1972: Mother of Sorrows Church, Centreville, Md.

1983: St. Dennis Church, Galena, Md.

Ordained, 1978

1978: St. Mary Magdalen Church, Wilmington.

1983: St. Francis de Sales Church, Salisbury, Md.

Ordained, 1955

1966: Father Judge High School for Boys, Philadelphia.

1978: Our Lady of Perpetual Help Church, Seaside Heights, N.J.

1980: Padua Academy, Wilmington.

1982: Our Lady of Good Counsel Church, Vienna, Va.

1991: St. Mary Church, Fredericksburg, Va.

1992: Seton Home School, Arlington, Va.

2001: Little Sisters of the Poor, Newark, Del.

Ordained, 1964

1964: St. Edmond's Church, Rehoboth Beach.

1964: Immaculate Conception Church, Elkton, Md.

1966: Holy Cross Church, Dover.

1968: St. Mary of the Assumption, Hockessin.

1970: Catholic Information Center, Wilmington.

1971: Diocesan Religious Education Center, Wilmington.

1974: Christian Formation Department, Wilmington.

1976: St. Francis de Sales Church, Salisbury, Md.

1986: Diocesan headquarters, Wilmington.

1990: Holy Family Church, Newark.

2001: St. Mary Magdalen, Wilmington.

Ordained 1960, died 1996

1960: St. Francis de Sales Church, Salisbury, Md.

1963: St. Catherine of Siena Church, Wilmington.

1965: St. Elizabeth Church, Wilmington.

Ordained 1957, died 1994

1957: St. Edmonds Church, Rehoboth Beach.

1958: Immaculate Conception Church, Marydel, Md.

1960: St. Thomas Church, Wilmington.

1961: St. Hedwigs Church, Wilmington.

1964: Holy Rosary Church, Claymont.

1971: St. Michael the Archangel Church, Georgetown.

1973: St. Mary Refuge of Sinners, Cambridge, Md.

1975: Holy Cross Church, Dover.

1976: St. Francis de Sales Church, Salisbury, Md.

1976: Delaware State Correctional Institute, Smyrna.

1985: St. Polycarps Church, Smyrna.

Ordained, 1979

1979: St. Francis de Sales, Salisbury, Md.

1979: St. Mary Refuge of Sinners, Cambridge, Md.

1980: St. Catherine of Siena, Wilmington.

1983: St. Johns-Holy Angels, Newark.

1987: Archdiocese of Philadelphia, Philadelphia.

Ordained, 1968

1959: Bishop Duffy High School, Niagara Falls, N.Y.

1961: De Sales Hall, Hyattsville, Md.

1962: De Chantal Hall, Lewiston, N.Y.

1964: De Sales Hall, Hyattsville, Md.

1968: Bishop Ireton High School, Alexandria, Va.

1973: Salesianum School, Wilmington.

1986: Archbishop Wood High School, Warminster, Pa.

1990: Weston School of Theology, Cambridge, Mass.

1991: St. Paul the Apostle Parish, Greensboro, N.C.

Ordained, 1981

1981: Immaculate Heart of Mary Church, Wilmington.

1986: St. Matthew Church, Wilmington.

1989: Holy Rosary Church, Claymont.

1992: St. Mary Magdalen Church, Wilmington.

1995: Corpus Christi Church, Elsmere.

1975: Bishop (now St. John) Neumann H.S., Philadelphia.

1982: Archmere Academy, Claymont.

1997: Archmere Academy, Claymont.

1996: Immaculate Conception Priory, Claymont.

Ordained, 1985

1985: Our Lady of Fatima, New Castle.

1986: St. Marks High School, Wilmington.

1987: St. Francis de Sales Church, Salisbury, Md.

1991: St. Johns Holy Angels Parish, Newark.

1993: Our Lady of Good Counsel Church, Secretary, Md.

1994: Holy Family Church, Newark.

1997: Holy Spirit Church, New Castle.

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.