Second Chances

Confidential diocesan records show church leaders repeatedly allowed known

pedophiles to return to ministry. Victims say their lives were altered

permanently.

By Rachanee Srisavasdi, Andrew Galvin, Tony Saavedra, and Chris Knap

Orange County Register

May 18, 2005

http://www.ocregister.com/ocr/2005/05/18/sections/news/news/article_523948.php

[This article is based in part on documents that the Orange diocese was

required to release. BishopAccountability.org has provided links to those

documents in the text below. The article discusses the files of Widera,

Ramos, and Pecharich.

For links to other Orange documents, see William Lobdell and Jean Guccione,

Orange Diocese

Gives Details on Sex Abuse; Gustavo Arellano, King

of the County Pedophiles; and Arellano's Personnel

Bile series.]

Diocese of Orange leaders enabled the sexual abuse of Catholic children

by accepting or keeping known pedophiles in parish work, by ignoring warnings

about abusive priests and by misleading parishioners, a review of church

records shows.

Fifteen once-sealed personnel files, made public Tuesdayas part of a record $100 million settlement of child sexual-abuse cases, provide a window into the minds of men of the cloth in Orange County from the 1960s to 1990s. A judge ruled the diocese must release other secret documents, including psychological reports and correspondence between church leaders, within a week.

|

| FOUND A CAUSE: Joelle Casteix listens

to Bishop Tod Brown during a news conference after the non-monetary

component of the trial Tuesday. Daniel A. Anderson, The Orange County Register |

The details of many of the cases have been revealed in lawsuits and previous news stories: boys sodomized by priests they trusted; a high school girl impregnated and given a sexually transmitted disease.

|

| “IT WAS WRONG”: Diocese of

Orange Bishop Tod Brown speaks to reporters and child-abuse complainants

at a news conference in Los Angeles on Tuesday. He said responses

on the part of the diocese were inadequate and failed. Daniel A. Anderson, The Orange County Register |

But other cases are new: A man who alleges he was molested for three years by a priest who later died of AIDS. That man received the highest settlement of any of the 90 victims: $3.7 million.

The files also reveal the extent to which diocesan bishops, chancellors and other church leaders routinely forgave priests for abusing children, paid for counseling, then welcomed them back to pastoral work - sometimes two or three times.

Former diocesan leaders have apologized for keeping accused clergy in ministry, saying they believed at the time they were doing the right thing. But in a news conference Tuesday, Orange Bishop Tod Brown acknowledged that those explanations were insufficient.

"The information contained in these documents is a painful testimony to the abuse suffered by the victims and the inadequate and failed responses on the part of the diocese in some cases in these years," Brown said.

"No amount of explanation about the past can stand in the light of what we now know about the sexual abuse of minors, nor can it assuage the pain inflicted on them and their families. It was wrong. Now, we must do all we can to heal."

The thousands of pages of confidential church records were a crucial component of the January settlement with 90 individuals who say they were abused by 45 priests, nuns, lay ministers, lay teachers, a brother and a school caretaker. The records include letters, memos and handwritten notes that detail church leaders' knowledge and discussions with the priests who served under them.

The diocese initially agreed not to oppose release of records it had revealed during settlement negotiations. But in the past week, the diocese began to raise a series of legal objections that would have scaled back the number of documents released.

Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Peter D. Lichtman ruled Tuesday that the diocese cannot scale back its document release and ordered the diocese to go even further, releasing psychological reports and letters between church leaders that it previously argued were confidential under privilege laws.

Five priests and three lay people had objected to the release of their own files, citing privacy rights, and Lichtman ruled Tuesday that he did not have the authority to release them. He left the door open for plaintiff's attorneys to appeal that ruling.

Sex offenses no bar to parish work

The files show that diocesan officials knew that at least three priests they accepted to work in Orange County had previously been in trouble for sexual abuse of children in other dioceses.

Take the case of the Rev. Siegfried Widera.

Diocese officials have said they knew Widera had "a moral problem having to do with a boy in school" before he came to Orange County in 1976.

But the records released on Tuesday show, for the first time, that church leaders knew much more than that.

Widera's file shows he was twice accused of abusing boys in Milwaukee and criminally convicted in 1973 of molestation. He was barred from working in Wisconsin parishes. [For two very different descriptions of these facts, see Widera's own 10/16/85 Personal History Sheet (p. 6) and Milwaukee archbishop Cousin's 12/20/76 letter to Orange chancellor Driscoll.]

When he came to visit his brother in Costa Mesa in 1976, the then-Archbishop of Milwaukee, William Cousins, called Bishop William Johnson and suggested that Widera might work in Orange County. [The call is referred to in Cousin's 12/20/76 letter.]

In a December 1976 letter to Diocese of Orange Chancellor Michael Driscoll, Cousins wrote of Widera's "moral problem" and said that the priest had a second such incident. He added "there would seem to be no great risk in allowing (Widera) to return to pastoral work."

Driscoll met Widera the following month and accepted him on the spot. Widera's first assignment was St. Pius V in Buena Park.

That same year, Widera began abusing Orange County boys, some as young as 9, according to lawsuits later filed in Orange County.

In 1985, Driscoll was told that someone witnessed Widera molest four or five boys in a swimming pool.

Two months later, in September 1985, Driscoll received a call from a woman in Yorba Linda who said her son had been touched inappropriately when Widera tucked him into bed.

The diocese removed Widera and sent him to a treatment facility in New Mexico.

As reports of abuse by Widera began to pile up at Marywood, the diocesan headquarters, Widera disappeared. In May 2002, prosecutors in Wisconsin filed nine counts of child molestation against him. Five months later, Orange County prosecutors filed 33 counts.

In May 2003, police found Widera in Mexico. While being questioned by Mexican police, he fell to his death from the third-floor balcony of a Mazatlan hotel.

This year, the diocese paid $17.7 million to nine men who alleged they were abused by Widera.

Earlier this year, one of Widera's victims, David Guerrero, told the Register how his life had been derailed by the years of abuse that began when he was 9.

"I needed help, and no one was there to help me," Guerrero said.

|

| David Guerrero |

Driscoll, who is now the Bishop of Boise, declined to be interviewed for this story.

But earlier this month, he posted a lengthy apology on his diocesan Web site.

"I am ashamed that this happened," Driscoll wrote. "It is hard for me to understand today how we could not have seen what was happening to the children."

Church leaders believed that abusive priests could be cured through treatment, and often ignored warnings from parishioners that suggested a different truth, the records show.

Like Widera, the Rev. Eleuterio Ramos had already been in trouble before coming to Orange County - a lawsuit claims he molested an 8-year-old boy at Resurrection Church in East Los Angeles.

Documents from his personnel files show that the Archdiocese of Los Angeles sent him for psychological treatment - "this care was suggested by the district attorney." He was then sent to Orange County, where he became a parish priest at Immaculate Heart of Mary in Santa Ana.

By late 1979, mothers and teachers were complaining to Bishop Johnson about Ramos' behavior.

Driscoll's notes from a phone conversation sketch the incident: "Boys taken to rectory ... some drinking ..."

Lawsuits settled by the church are more explicit: Ramos was accused of taking boys to drive-in movies and motels, giving them alcohol and pornography, then orally copulating them.

Diocese officials sent Ramos to Maryland for treatment in December 1979. [In fact, Ramos was sent to Rev. Michael R. Peterson's St. Luke Institute at Marsalin in Holliston MA, which was a clinic run by Sy. Luke Institute of Suitland MD. The earliest evidence of this arrangement is a 12/3/79 letter from Peterson to Bishop Johnson.]

In April 1980, Bishop William R. Johnson revealed his own feelings about Ramos in a letter to the director of the treatment center. Johnson called Ramos "a fine priest, zealous and generous hearted. ... He will be returning to the Diocese early next month and we look forward to having him back with us," Johnson wrote.

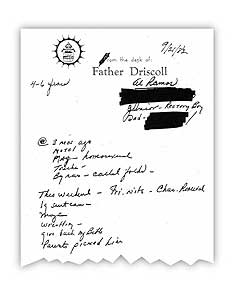

|

| This 1982 note from the desk of then-Chancellor Michael Driscoll describes a complaint against Ramos. |

According to lawsuits, Ramos would continue to abuse boys for the next five years, in one case allowing other men to join in the abuse in a Mexican hotel room.

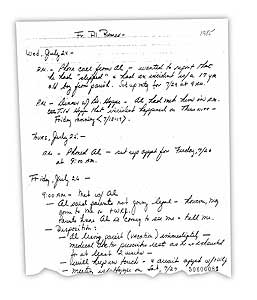

|

| This unsigned 1985 document describes a phone call in which the Rev. Eleuterio “Al” Ramos admitted that he had “slipped” and had an incident with a 17-year-old boy. Ramos left the parish days later. |

Finally, a boy told his parents.

Bishop Johnson arranged for Ramos to be placed at a church in Mexico. The Diocese continued to give Ramos a monthly stipend of $500 until 1992, records show.

Parishioners who had been warning Driscoll and Johnson about Ramos for years remained angry at how long it took for Ramos to be removed.

"The Diocese took their time in doing it. ... The Bishop or Msgr. Driscoll (told) me they needed four people to corroborate our statements," wrote a woman whose name was blacked out.

Ramos eventually confessed to police that he molested more than 20 boys.

He died in 2003.

The diocese reached a secret settlement with two people in 1993 and 1994. Earlier this year, it settled with 11 more - for $16.6 million.

Church leaders repeatedly downplayed complaints logged against some priests, the records show. The files contradict public statements made by the diocese about at least five accused abusers.

In the case of the Rev. Michael Pecharich, the founding pastor of San Francisco Solano Church in Rancho Santa Margarita, documents released Tuesday indicate the diocese received multiple complaints of inappropriate behavior by Pecharich before he was removed from ministry three years ago.

The diocese learned in 1996 that Pecharich had zipped himself into a sleeping bag with a boy on a 1984 camping trip and then fondled the boy. [See the victim's complaint letter and Chancellor Urell's notes on his meeting with the victim.]

In March 2002, Brown announced the implementation of a "zero-tolerance policy" against known molesters.

"Although there have been no further instances of misconduct, nor any new accusations, the Diocese has taken the position that any priest who was ever involved in this kind of behavior cannot serve in ministry," Brown said.

But the records released Tuesday show that the diocese had numerous other reports of behavior by Pecharich that left onlookers "scandalized," in the words of one parent.

The records show Msgr. John Urell met with Pecharich about one interaction in August 1995, in which a boy complained about the priest's hugs. [The victim was a 28-year-old seminarian in 1995 when he wrote his complaint letter and met with Pecharich and Chancellor Urell, who took notes. The victim was 15 or 16 years old during the counseling sessions at which Pecharich hugged and kissed him.]

"He had no [']intentions['] in anything he had done ... he is more aware now about how actions are perceived; and how others can 'experience' something in a different way than it was intended," Urell wrote.

In a separate incident [in fact, this is the same complaint], one young man alleged Pecharich hugged and kissed him on the cheek during counseling sessions while Pecharich was a pastor at San Antonio de Padua Catholic Church in Anaheim Hills.

"It is true he did not molest me, but his behavior with me was, to say the least, inappropriate. He crossed sexual boundaries, and that was wrong," the youth wrote. [See again the seminarian's complaint letter.]

While Pecharich was at San Francisco Solano, the diocese also received complaints that Pecharich "put his hands in the back pocket of a young boy and stood there talking to him," according to a March 1996 letter to Bishop Norm McFarland.

"He approached our son and pulled hair off his leg and told him to put it on his chest," the parent wrote. "We won't begin to speculate what motivates Father Michael's inappropriate conduct. ... Our children were scandalized and shocked a priest would behave in such a manner."

These complaints didn't seem to affect Pecharich's standing. Bishop Brown appointed Pecharich in 2000 to the Committee for the Removal of a Pastor.

Brown said Tuesday that he did not see Pecharich's file before 2002, the year Pecharich was removed.

After Pecharich's removal, two other people came forward and said they were molested by Pecharich. One parishioner wrote to ask why Pecharich was allowed to remain as long as he was.

"We see that Mr. Pecharich is gone. What is clearly missing is an explanation for why he was ever allowed to come into contact with our children when his background and sickness were known to the [D]iocese," a parishioner wrote Brown. "Who made such decisions? Moreover, if the men who allowed Mr. Pecharich to be our priest are still empowered in the Diocese, how can we truly be certain that such breaches of trust will not again take place?"

Pecharich could not be reached for comment.

Bishop Brown reiterated Tuesday that the diocese has changed the way it handles reports of sexual abuse.

"These stories are about what was wrong then. The release of these documents is about getting it right now," he said.

CONTACT US: rsrisavasdi@ocregister.com or cknap@ocregister.com

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.