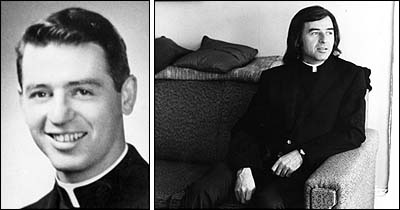

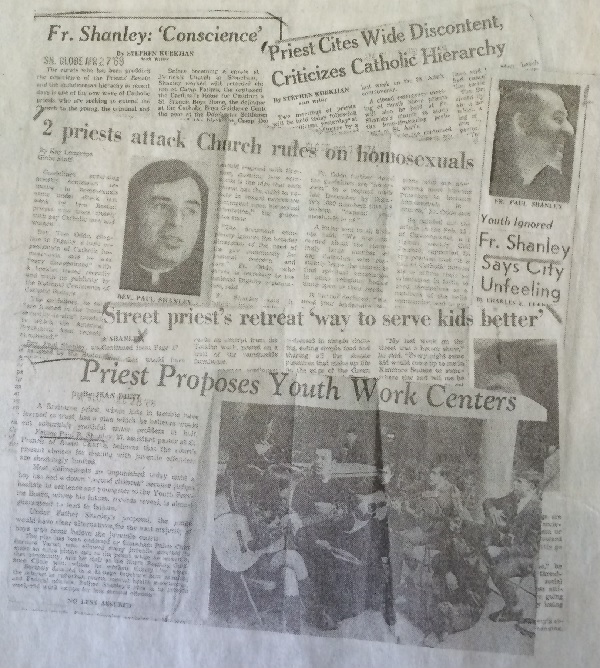

By Sacha Pfeiffer [See Scores of priests involved in sex abuse cases, by Walter Robinson, Boston Globe, January 31, 2002, with links to other articles that appeared on the same day. See also Shanley's record long ignored: Files show Law, others backed priest, with links to documents, by Walter V. Robinson and Thomas Farragher, Boston Globe, April 9, 2002; and our detailed assignment record of Shanley with links to the documents.] Boston's Catholics had never seen a priest quite like Paul Shanley. Handsome and charismatic, he wore his hair long, growing thick sideburns and shedding his Roman collar for plaid shirts and jeans. He openly questioned church teachings, particularly its condemnation of homosexuality, clashing often and publicly with his superiors, including then-Cardinal Humberto Medeiros. He espoused radical views in a city deeply wedded to tradition, and his was a voice of defiance in an institution where obedience is sacred. Known as Boston's street priest in the 1960s and '70s, he created a "ministry to alienated youth" for runaways, drug abusers, drifters, and teenagers struggling with their sexual identity. But in the parishes and counseling rooms where desperate and troubled young people sought his help, the Rev. Paul R. Shanley was a sexual predator. In interviews with four people who said they were abused by Shanley, as well as their families and lawyers who have settled at least three sexual abuse claims against him with the Archdiocese of Boston, the same stories repeatedly emerged: rape, molestation, and coerced sex in which Shanley used his power and authority to prey on those who came to him for guidance and support. One of Shanley's victims, now 42, met him when he was 15 to discuss his difficult family life. The man, who asked not to be identified, said the session ended in a strip poker game – "to help you feel comfortable with your body," he said Shanley told him – that led to sex. Another victim, 53-year-old Arthur Austin, who has a pending claim against Shanley, said he went to the priest for counseling after his first gay relationship ended when he was 20. He was given "access" to Shanley's body to ease the pain of the breakup, Austin said Shanley told him. Two siblings of a third alleged victim said Shanley molested their brother, then a Stoneham teenager, at a cabin in the Blue Hills in Canton in the late 1960s. Shanley called the abuse "the Lord's work to find out who the homosexuals were," they said. Shanley's story is among the most insidious cases of clergy sex abuse found by the Spotlight Team. The number of his victims is unclear. But in four decades as a priest, he often worked exclusively with adolescents, and his much-publicized youth ministry attracted countless young people with its counterculture mission. Yet when family members of Shanley's victims notified top church officials of the abuse, they were met with silence – just as complaints about now-defrocked priest John J. Geoghan were ignored by the archdiocese. Shanley, who is now 70 and lives in San Diego, has an unlisted telephone number and could not be reached for comment.

The Rev. John J. White, a retired priest in Billerica contacted by the Globe because he lived with Shanley in a house they co-owned in Palm Springs, Calif., in the 1990s, said he notified Shanley by telephone Monday that the Globe was trying to reach him. White initially denied he had owned property with Shanley – until he was told public records show otherwise. Donna M. Morrissey, spokeswoman for the archdiocese, said the church would not comment on Shanley. Shanley's career, which began with his ordination in 1960, included parish appointments at St. Patrick's in Stoneham and St. Francis of Assisi in Braintree, followed by the chaplaincy at Boston State College in 1969. That same year, Shanley established a retreat house for youth workers on a 95-acre farm in Weston, Vt., and named it Rivendell after the peaceful valley in J. R. R. Tolkien's "The Hobbit." In 1970 he launched his "ministry to alienated youth," based at St. Philip's in Roxbury. He ran the ministry for eight years, attracting wide public attention for embracing ostracized minorities and challenging the church's position on homosexuality. Photos of the dashing, shaggy-maned "Father Paul" appeared often in local papers, including the Globe. At the time, Shanley lived in an apartment on Beacon Street, where several of his victims say his abuse took place. In 1979, Medeiros reassigned Shanley, naming him pastor of St. Jean-St. John Parish in Newton – even though in 1974, according to one of Shanley's victims, the cardinal had been notified of Shanley's abuse by the victim's mother. Shanley said publicly at the time he was removed from the youth ministry because he differed with Medeiros over the church's outreach to homosexuals.

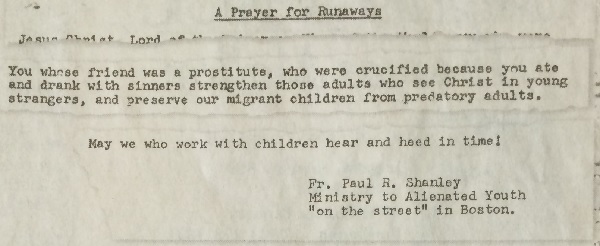

Ten years later, he left for a "sabbatical" in California, surfacing at St. Ann Parish in San Bernardino. Another priest at the Newton church, the Rev. Daniel J. Cavanaugh, said at the time that Shanley left because of a stomach ailment. Church directories list Shanley on "sick leave" from 1990 to 1995. Asked about Shanley's illness, White, the Billerica priest who lived with Shanley in California, said Shanley suffered from "allergies." For three or four years in the mid-'90s, according to church directories, Shanley was acting director of Leo House, a guest house for clergy, students, and travelers in New York City. According to a lawyer knowledgeable about Shanley's case, the Boston Archdiocese ordered Shanley to leave Leo House and threatened to cut off his health insurance after learning he was still working in a setting that put him in contact with young people. Church directories indicate Shanley is now assigned to archdiocesan headquarters in Brighton, although church officials acknowledge he is living in California. Among those coping with the aftermath of Shanley's abuse is Austin, who said he first met Shanley in 1968 at the St. Francis rectory to talk about his breakup with his first gay lover. Shanley made "peculiar" inquiries, Austin said, about his genitalia and the details of his homosexual experiences. "Even as emotionally distraught as I was, I remember thinking that they were very strange questions," Austin said. "But he was a priest, and I thought it was something he needed to know. Otherwise, why would he ask? I know how stupidly naive that must sound, but it's true." Austin said Shanley offered him "access to his body" to help heal the hurt of his breakup, and told him he would shoulder the "moral responsibility" of the offer. The next day, Shanley drove Austin to the cabin in Canton, where Austin said Shanley molested him. After that first episode, "I basically became Paul's sex slave," Austin said. "When he wanted me to service him, he'd call me up and tell me he was going to come pick me up." As the relationship continued, Austin said he grew more confused and distraught. He broke off contact with Shanley when he was 26, but fell into a depression he says he continues to battle. In 1998, after years of therapy, Austin reported the abuse to his pastor, who referred him to the Rev. William F. Murphy, the archdiocesan official who handled sex abuse complaints at the time. Austin said Murphy apologized for Shanley's actions and told him the church had received other complaints about Shanley. After what Austin said was "relentless" pressure from Murphy to accept a settlement in exchange for signing a confidentiality agreement precluding him from publicly discussing the case, he refused to settle and retained Boston attorney Laurence E. Hardoon, who has filed a claim on his behalf. Hardoon has settled two additional claims against Shanley. Reached yesterday, Murphy declined to comment on the case, but said he found Austin to be "sincere and credible." Another Shanley victim who lives in Boston's Back Bay – the 42-year-old man who requested anonymity because of the stigma associated with sex abuse – said he met Shanley the summer after his first year of high school, in 1974. One of five children who had spent several years in an orphanage, he said he went to Shanley's apartment to discuss his tumultuous home life and struggle growing up gay in Dorchester. He said Shanley suggested strip poker, saying it would put him at ease with his body. They stripped, then stood before a mirror and compared their bodies. The man said the visit marked the start of a seven-year sexual relationship in which Shanley also arranged sexual liaisons for him with other men. In a lengthy interview with the Globe, the man described his relationship with Shanley as "damaging, because oftentimes I wanted and needed to talk, and it was time for sex. I began to think sex was my worth because he was charming and handsome and respected, and that was his interest in me." Their meetings halted abruptly later that year, in the fall of 1974, when his diary, which detailed the abuse, was found by his mother, who gave it to Medeiros. The man said Shanley later told him he had been threatened with excommunication by Medeiros. It was not until four years later that Medeiros, who died in 1983, removed Shanley from the youth ministry. But Medeiros reassigned him to Newton. The man – who said he felt "enormous guilt" because he believed he had damaged Shanley's career – called Shanley several months later. "He told me he wasn't supposed to see young people," the man recalled. "He said, 'Do you want to see me?' I said yeah. He said, 'OK, but you can't tell anyone."' They met at Shanley's apartment and he said the abuse continued, lasting until the man ended the relationship when he was 23. Years of anger, depression, and heavy drinking followed, he said. Reluctant to dredge up memories of the abuse, he said he has not filed a lawsuit or contacted a lawyer. Another Shanley victim, a Stoneham man who died in 1998, was also abused at the Canton cabin while Shanley was assigned to St. Patrick's, according to his siblings. The man's brother and sister contacted the Globe separately, one by telephone and one by e-mail, to report Shanley's abuse. Until told by a reporter, each was unaware the other had called. Both initially said they were willing to allow their names to be published, but they later asked for anonymity at the request of their elderly mother. After molesting the man, Shanley, despite his public support of homosexuals, would "tell him he was doing the Lord's work to find out who the homosexuals were and tell him he would burn in hell for what just happened," according to the man's brother. Both siblings said their brother suffered severe psychological aftereffects of the abuse. But they said he refused to notify church officials or contact an attorney. "I used to tell him all the time to go to the church and a lawyer, but he wouldn't," the man's brother said. "There was probably a whole lot of shame still attached to it." The sister of another Shanley victim, who settled with the archdiocese in 1993, said that when her brother was 11, around 1969, their mother sent him to Shanley at St. Francis after he had run away. She said Shanley abused her brother in his office, but her brother didn't reveal the abuse to her and other family members until the 1990s. "My brother thought it was a sin," she said. Around 1995, the victim's mother told the Globe, she wrote to Law, pleading for help, but received no reply. "He never had the decency to answer it," said the mother. Because of a confidentiality agreement signed by the victim, both women requested that their names not be published. "I feel guilty about what happened to my son because I was friendly with Paul Shanley," the mother said. "My son left home and needed counseling, so I sent him to Shanley. ... I feel guilty that I am partly responsible for this happening." Even after Shanley left Boston, "he had the nerve to write me a letter telling me where he was in Vermont, and that any time my son wanted to come up, he could. He even told me what bus," the woman said. She provided the Globe with a copy of a prayer written by Shanley in 1970. Titled "A Prayer for Runaways," it includes this line: "You whose friend was a prostitute, who were crucified because you ate and drank with sinners strengthen those adults who see Christ in young strangers, and preserve our migrant children from predatory adults." [See the entire prayer, in a Shanley newsletter.] This story ran on page A21 of the Boston Globe on 1/31/2002. |

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.