Faith Betrayed

The Lafayette Diocese has been home and haven to men of God who shattered

lives and walked away

By Linda Graham Caleca and Richard D. Walton

Indianapolis Star

February 16, 1997

[See links to all

the articles in this series from the Indianapolis Star.]

In the heart of Indiana lies a Roman Catholic diocese tainted by priestly

sins, dark secrets of lust and betrayal that have wounded scores of victims.

Even more painful, for some, has been the church's response.

Instead of compassion, they found cover-up.

Instead of justice, they watched their abusers go free.

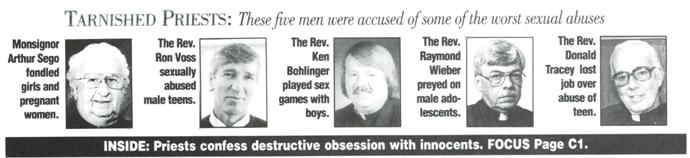

The Rev. Ken Bohlinger, who masturbated with boys, now sells luggage in Arizona. The Rev. Ron Voss, who sexually abused male teens, moved to Haiti. Monsignor Arthur Sego, who fondled girls, was retired to a Missouri rest home.

Other priests of the Lafayette Diocese are back in their pulpits after they were accused of sexually exploiting vulnerable adults. Some priests pursued relations with parishioners or fellow priests. A few lured teens with alcohol and pornography.

One priest had sexual relations with a teen who went on to become a priest himself. After donning the collar, that victim also became a sexual predator, abusing male adolescents, His name: Ron Voss.

An investigation by The Indianapolis Star and The Indianapolis

News revealed that at least 16 current and former priests have been

accused of sexual abuse or misconduct during the past 25 years. Forced

out of silence by the newspapers' investigation, diocese officials admitted

to 12 troubled priests and as many as 40 victims in the past dozen years

alone.

All this in a diocese with just 75 active priests.

|

The accused were men pledged to celibate lives, devoting their minds

and bodies fully to God. They were trusted and revered by parishioners

in a diocese spanning 24 counties in north-central Indiana, from the northern

suburbs of Indianapolis to tiny Wheatfield.

An expert on sexual misconduct among priests was disturbed at the scope

of the problem in this mostly rural diocese.

Nationally, just 2 percent to 3 percent of priests are ever accused of such misconduct, says Dr. Fred Berlin. director of a leading sexual disorders clinic at The Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore.

In the Lafayette Diocese, the rate is no less than 16 percent — even factoring in priests long retired.

Says Berlin, who advises the National Conference of Catholic Bishops: "That's an awfully high percentage — the highest I've seen."

Perhaps even more surprising, though, is how quiet the problem has been kept.

Few among the faithful ever learned of these widespread abuses. Bishops have not reported most acts to the public, parishioners or even their own clergy. In the churches where some of the abusers served, their secrets were hidden to this day.

The current leader, Bishop William L. Higi, has worked to move the diocese out of a pattern of neglect. He has banished the worst abusers and effectively ended their ministries. To root out molesters, he requires priests to sign affidavits stating whether they have ever been accused of child abuse. For victims, Higi offers a toll-free hotline and counseling.

Yet the 63-year-old Higi keeps mum about molesters in his diocese until forced to acknowledge them. He fails to fully account for who and how many have been hurt. And though he speaks movingly about the agony of child abuse, he conceals the details a community needs to reach out to its victims.

By Higi's silence, parents do not know enough to ask their children whether a priest has ever touched them sexually. By his silence, there is little or no public outrage, the kind that drives prosecutors to act. By his silence, some perpetrators are allowed to slip out of town quietly and begin new lives.

Predators of children and teens avoided prison. Even priests who confessed to abusing multiple victims escaped criminal prosecution and scandalous trials.

The harshest punishment suffered by any accused priest befell Sego. Facing the threat of a lawsuit by an angry victim, Sego was forced by Higi into a restricted lifestyle at a rest home near St. Louis. Though Sego can say Mass inside the home, he is barred from publicly functioning as a priest.

That is not nearly good enough, say victims. They charge they are left with no say in their abusers' punishment, no monetary damages for their suffering and only rare public admissions of the pain they endured.

"The more you disavow, the more you say, 'Be quiet,' the more everyone suffers." says Sego victim Linda Schrader.

|

|

| Befriended, Betrayed: As a girl, Angela Mitchell trusted her priest at St. Patrick Church in Kokomo. Father Arthur Sego was by her side on the proud day of her First Communion. Sego often told the lonely girl he loved her. But when they were alone, he abused her. At right, Mitchell, now 36, fights back tears as she talks of her molestation. She says the priest was interested in her skin condition and photographed her body. |

Trail of shame

Some frustrated priests fear the damage wrought by their bishops' past and present mistakes has crippled the diocese.

The Rev. Melvin J. Bennett links the years of misconduct and secrecy to low morale among the clergy, eroding trust in the priesthood and a shortage of seminarians. While dioceses nationwide are hurting for seminary students, the problem is acute in the Lafayette Diocese: Only four seminarians are expected to be ordained through the year 2000.

|

"There are some of us who feel that the Holy Spirit has spoken with this diocese," says Father Bennett of St. Bernard Church in Crawfordsville.

"We are in crisis now."

Bennett, 55, a veteran priest who has held positions of responsibility within the diocese, prayed for guidance before airing his concerns. He is more outspoken with his criticisms than other priests, who commented for this series but feared reprisals from the bishop if they were quoted by name.

One such priest says it is misguided to believe that revelations of misconduct will bring ruin to a church rooted in the Gospel.

"We keep thinking that this church is going to be damaged by the truth." he says. "No! The church is set free by the truth."

The Star and The News tracked sins of the fathers back to 1956, a dozen years after the Lafayette Diocese was established. That is when Sego began asking pregnant young women who came to him for counseling to strip. So "fascinated" was he by their pregnancies, Sego later admitted, that he photographed and fondled the expectant mothers.

Sego moved from church to church, preying on young women and girls. Kokomo's Angela Mitchell was just 9 or 10 when, she says, the priest forced her to masturbate him. Sego, who was curious about the child's body because she suffered a disfiguring skin condition, admits to some acts with Angela but says masturbation was not one of them.

Mitchell, now 36 and the mother of a young son, insists it is true.

"He had me do it. With my hand. My hands would be wet."

"How a person could get any kind of pleasure out of a child is beyond me," she says.

Suspicions about Sego were long silenced by church officials.

Concerns about the Rev. Raymond Wieber, who died in 1993, festered for years.

Wieber, of St. Lawrence Church in Muncie, was accused of preying on male adolescents. Some of them attended a popular youth program he ran during the 1970s from a house on Wheeling Avenue.

Wieber collected teens in the basement of that house and then chose his victims one by one, according to an abuse victim who told his story to a Muncie woman. "I want him stopped," the accuser told Phyllis Marlowe, a devout Catholic who long suspected Wieber.

For years, Marlowe tried unsuccessfully to enlist others in her crusade to get Wieber removed from the pulpit.

No one helped her. Says Marlowe, now the Delaware County recorder: "They just didn't believe me."

Wieber was allowed extraordinary access to youths despite warnings about his character even before he was ordained. The warnings were noted in Wieber's personnel file, says Merrillville attorney Michael Baechle, who represented a victim. Far from supervising the unfit priest, Baechle says, church officials just "turned him loose."

Then there was Voss.

During the 1970s and '80s, the priest led a family camp in rural Delaware County. The charismatic peace activist sang songs of hope and preached social justice, inspiring adult campers — and impressing their children.

Brazenly, with adults nearby, Voss invited teen-age boys to his tent or cabin. There, he engaged in "inappropriate touching and sexual manipulation," says diocese Vicar General Rev. Robert Sell, who investigates sexual abuse and misconduct cases. While Sell insists those youths were between the ages of 16 and 18 — past the legal age of consent — other sources put some of the victims' ages at 14 and 15.

As a teen growing up in Anderson, Voss himself had sexual relations with a priest. Voss admitted that to several people, including the mother of one of his victims. Voss would not talk to The Star and The News about the teens he abused, but in a letter circulated to friends in 1993, he apologized for his "past inappropriate behavior" and for being "'a source of great pain."

|

| Fallen Leader: Ron Voss' family camp drew parents and adolescents from Indiana and beyond. Families were crushed to learn he sexually abused male teens. Voss never was prosecuted and is a free man in Haiti. |

A silence broken

While the true human toll of abusive priests might never be known, the diocese acknowledged it helped pay for the therapy of up to 40 victims, a number officials later said could be as low as 20.

Voss alone had eight alleged victims, by the diocese's own count. It is unclear how many girls, teens or young women Sego abused.

In a court deposition, Higi put the number of Sego accusers at 15 or 16. Sego, under oath, acknowledged just five accusers, along with the pregnant women he fondled. In recent interviews, he confirmed two victims, then said there was only one — Angela Mitchell.

No hint of Sego's abuses seeped out until 1994, when Mitchell confronted the priest, then sued him. Until now, the scope of Sego's molestations went unsaid.

Wieber's offenses, too, began to surface only when an altar boy sued him shortly before the priest's death.

No lawsuit flushed out Voss, who received therapy but continued as a priest either in Indiana or Haiti for five years after he was first accused of sexual abuse. They were years of silence by Bishop Higi.

Only now is another sexual abuser, Father Bohlinger, revealed.

Bohlinger admitted to The Star and The News that, as a priest at St. Mary Church in Anderson during the 1980s. he took boys on camping trips, supplied them with alcohol and pornography, then played sex games with them in his tent. He said they went along because he was a priest — "someone they trusted."

Bohlinger was candid about his problem but evaded certain issues, such as the number of young people he victimized. He said only that it was fewer than "dozens." He did not name all the churches the youths attended.

While flatly denying having had intercourse with his victims, he answered "no comment" when asked whether there was oral sex.

"Face it," said Bohlinger. "I was one of the worst priests ever ordained."

Higi, upon learning of an old accusation against Bohlinger in 1988, immediately removed him from St. Joseph Church in Rochester and sent him to therapy. But the bishop kept Bohlinger's abuses quiet for eight years — until questioned for these stories.

Bohlinger told the newspapers he stopped sexually exploiting minors in 1986. He no longer functions as a priest and lives a solitary life in Arizona. He says he takes pains to steer clear of children.

Still, he admits he will never be cured.

"It's the old day-by-day," he says.

Sexual misconduct is hardly limited to the priesthood. In fact, experts say the typical child abuser is a married man. Still, few professions have the kind of access to children and other vulnerable people granted to men of the collar. And the Catholic Church historically has been secretive about its abusers.

So little is said to so few in the Lafayette Diocese that even many fellow priests did not know why Father Bohlinger suddenly disappeared from his church. Priests say they often do not learn about charges until years later. That prevents them from ministering to accused brethren, much less to their victims.

Bennett, the outspoken Crawfordsville priest, says he wants people to know that if priests do not respond in a caring way when accusations arise, it is because they are left uninformed.

"We are completely in the dark," he says.

They clearly were in the summer of 1995.

That is when a sexual misconduct case exploded on the bishop.

Revolt from within

Higi had decided to quietly handle an accusation against the Rev. Robert E. Moran. A former Purdue University student accused Moran of taking advantage of him when he went to the associate pastor for counseling in a time of grief in 1980 at St. Thomas Aquinas Church in West Lafayette.

The student went on to have a 15-year sexual relationship with Moran and, with Moran's help, to become a priest himself. Only then did that young priest say he realized Moran had exploited his power over him at a vulnerable time and that his own years in the ministry had been a farce.

Higi saw no abuse because the affair began when the accuser was 19 years old — a "consenting adult" in the bishop's eyes.

So Higi bypassed a board of priests and lay people he had created to advise him on sexual misconduct cases. Noting that he had kept other adult cases from the Diocesan Review Board as well, Higi urged the panel to "have confidence in my judgment as bishop."

All the members promptly resigned.

When questioned by The Star and The News, Higi repeatedly claimed not to know why the board quit.

"I can only surmise," he told reporters in September. "I honestly don't know. They resign, they resign."

Higi's assertion, though, contradicts his own correspondence from the previous year.

Reporters reviewed letters between Higi and a priest board member, the Rev. Richard Weisenberger, that dealt explicitly with panel members' concerns over the Moran case and their threat to resign.

Weisenberger expressed frustration that the board had been "ignored," as well as fears that Moran could pose a threat to others who came to him for counseling.

"We have enough questions about this to wonder whether we can continue'' on the board, Weisenberger wrote Higi.

The bishop replied that the board did not know the whole story. He said he was dealing with Moran in his own way. and urged board members to trust him.

Moran, now at St. John the Evangelist Church in Hartford City after receiving extensive therapy, declined to be interviewed, as did his accuser.

Though the Diocesan Review Board was not consulted in that case, it has been in many others. Just creating it was a step forward from past practices of neglect.

For decades, the church did little to help victims or protect the public.

After a Kokomo mother complained about Arthur Sego in 1971, the late Bishop Raymond Gallagher sent the priest to therapy, then returned him to the church where he molested. That put Sego back at St. Patrick Church with his victim, Angela Mitchell.

Gallagher did one more thing — he enlisted young Angela's mother in a cover-up.

He wrote to Wanda Mitchell, reassuring her that the church was handling the problem. Urging her silence to protect both Angela and "Monsignor," the bishop advised: "Destroy this letter."

Gallagher's second-in-command at the time was an industrious priest working his way up in the chancery. His name: William L. Higi.

When it came time for Bishop Higi to choose his second-in-command, he named Sego.

While Higi said he was "flabbergasted" to learn in 1994 of Mitchell's charge that Sego was a molester, others are not sure what Higi knew and when he knew it. Priests in the diocese whisper that the bishop had to be naive or blind not to suspect. They note that Higi and Sego were close friends for decades. They have lived together in the bishop's house and traveled together to Florida and Europe.

Abuser Voss also was a longtime friend of Higi's. They grew up in the same neighborhood in Anderson. Higi says Voss feels deep regret for his wrongdoing and has been rehabilitated. The bishop praises Voss as a "success story."

When charges arose against Voss in the late 1980s, Higi did not consult his top aide, Sego.

A court document shows that Higi did not trust one friend's ability to hold his other friend's problems in confidence.

A question of motives

If secrets permeate this diocese, Higi's current second-in-command says there is good reason. Father Sell contends it is the diocese's duty to respect the confidential nature of accusations of abuse.

"It's not because we are choosing to be deceptive. It's because we have a reverential care for the individuals involved," he said.

Priests cite another reason for such caution.

They say a fear of lawsuits haunts Higi.

Even a supporter says the bishop frets over liability. The Rev. Leo Piguet of St. Elizabeth Seton Church in Carmel says Higi told him a single lawsuit could result in a settlement of a quarter-million dollars.

"I would say he is terribly distracted by it," and has been for years, Piguet says.

Money alone, one priest charged, motivated Higi to punish him.

The Rev. Gerald Funcheon, in a letter to The Star and The News, said Higi removed him from his pulpit when a family accused him of "planning" to molest their boy. Higi says only that he had a serious concern about Funcheon, then at St. Mary Church in Dunnington. "So he was busted." In a 1994 letter to the archbishop of St. Louis, Higi called the priest "unassignable" and noted that the situation was "not public."

Funcheon, in his letter to the newspapers, blamed his fall on Higi's tightfistedness.

"Bishop Higi concluded that in the present climate of multimillion-dollar lawsuits, he had no alternative but to send me away," Funcheon wrote.

Higi counters that no fear of lawsuits "exists in my heart." At the same time, he will not explain why he sends priests such as Funcheon away. He says few need to know details of sexual abuse cases, and he derides critics and reporters for seeking them. He says in exasperation that some would like him to "put an ad in The New York Times."

In the past, bishops kept silent partly out of ignorance. For example, so little was known about priest pedophilia that Higi says he never heard of it before becoming bishop in 1984.

"This entire thing," he says, "is a wrenching experience for me."

For the Catholic Church, too.

Jeanette Sears, a Catholic from Crawfordsville who knew Father Voss, thinks the church is unfairly criticized for doing too little about sexual abuse in years past when no one in society understood the problem.

Critics say "the church should have stopped this. The church should have known," she says. But the church is a forgiving church. So, Sears says, priests were forgiven and reassigned with the admonishment, "Go, and sin no more."

Now when a priest is accused. Higi says, he follows five rules. He says he responds promptly; relieves priests of their duties when evidence warrants and sends them for therapeutic evaluation; makes required reports to Child Protective Services or other authorities; reaches out to victims and families; and deals "as openly as possible" with the community.

In the Archdiocese of Chicago, discipline and victim outreach are taken a step further.

In addition to reporting child abuse charges to protective-service agencies, officials routinely notify criminal prosecutors. And the church makes it a priority to keep victims informed on the progress of investigations.

That's a weak point in the Lafayette Diocese, victims say. Some complain they cannot even get assurances that their abusers have been safely separated from children.

Higi says he tries hard to ease victims' fears and pain, but admits he hasn't always been effective.

He tried going public with parishioners just once in an abuse case — and his words offended.

In what he calls a remarkable initiative for a bishop. Higi went to two of Arthur Sego's former churches in 1994 to inform Catholics of accusations against the priest. But a victim's sister came away thinking Higi was just making excuses for the monsignor.

The bishop told the group that Sego was his friend, and he urged forgiveness, says Barb Keyes, a sister of Sego victim Linda Schrader. Yet Higi stopped short of admitting that "anything really happened," Keyes says.

Others vehemently defended the priest. A nun spoke of how good Sego was with children. She urged the group to "remember his smile."

"We walked away with the feeling that this guy was a saint," Keyes said. "I was seething. I knew the truth."

Forgiving the accused

The truth is that lives are ruined by molesters such as Sego. But victims are intimidated from coming forward. Devout Catholic families typically do not sue or press charges out of respect for the church or fear of public scandal. Other victims repress painful memories for years before realizing they are victims.

By the time some do seek legal advice, it is too late — the statute of limitations has run out.

So justice is left to Higi. He urges forgiveness, both for the accuser — whom some revile for accusing a priest — as well as for the perpetrator.

As for jail, the bishop is not sure abusive priests belong there. Incarceration, he says, "punishes a person, but does it do anything to make sure it won't happen again? I don't know. I question that."

Regardless, Higi says, it is not for him to sit in judgment on who is locked up and who is not. "That's a legal point." he says.

Angela Mitchell believes Sego should be in prison — not a rest home.

She says he belongs behind bars "for what he did to me alone."

Had Sego been tried and convicted of molesting young children, he could have served up to eight years in prison for each offense, says Tippecanoe County Prosecutor Jerry Bean. Each of Voss' offenses with victims who were 14 or 15 could have brought him three years incarceration.

Instead, the abusers live pretty comfortable lives.

Though Sego. 75, cannot leave his priest retirement home without supervision, victims complain that he is free to stroll around the scenic woods of his peaceful home.

When Sego asked Higi whether he still could be pictured in the 1996 diocesan handbook of priests, the bishop agreed. A smiling Sego is shown wearing his collar.

Voss is a respected figure in Haiti. In August, he was honored by a visit from Higi. The bishop spent time with the former priest, who works with the needy, during a trip to the island to inspect church missions.

"He is doing magnificent work," Higi said. "It's amazing what the man has been able to do."

Some priests from the Lafayette Diocese returned from trips to Haiti months earlier with a different view.

They reported comments from Haitians that Voss still might be celebrating Mass, and possibly even taking children home with him.

Their concerns drew a sharp written rebuke from the diocese last March. Sell, the vicar general, declared that Voss has stayed out of trouble and "kept constant vigilance over himself." Sell also said that since Voss resigned his ministry in 1993, he has not functioned as a priest and "directs individuals to cease from calling him 'Father.'"

Yet, in a 1994 national television appearance about violence in Haiti, a tanned and eloquent Voss was referred to as "Father Voss" and as a "priest from Indiana."

On CBS' Eye to Eye With Connie Chung, Voss spoke for his adopted strife-torn country. Shown strumming his guitar and singing with a group of Haitians, Voss was depicted as a man of conscience who lost a friend to the violence, and who "knows all about the reign of fear."

While sex abuser Voss addressed an audience of millions, the concerned priests in Indiana were silenced.

Citing a church canon that defends the honor of priests, Sell ordered them to "cease from jeopardizing the name and reputation of Ron Voss."

Dozen troubled men

That kind of emphatic denial is typical of Higi's administration. some priests say.

Even while admitting to The Star and The News that 12 of his priests had violated sexual "boundaries" since he became bishop in 1984, Higi minimized some of the offenses, blaming misdeeds on the "human condition." He said pedophilia will never be tolerated. But while refusing to describe other acts, he suggested some were no more serious than a hug.

|

Tough Decisions: Bishop William Higi says he acts responsibly in abuse cases, even if some disagree. Staff Photo / D. Todd Moore. |

"We live in a very interesting world where people can misunderstand the most innocent of actions," the bishop said.

According to Higi, 14 of his priests have been accused since 1984. Two men were judged innocent, leaving the dozen troubled priests. Figuring he has 100 active and retired priests, "that's 12 percent of my clergy." Higi said.

The 16 percent found by the newspapers also was based on 100 active and retired priests, the diocese's average over the past 25 years.

Higi would not name his 12 offending priests, so it is not known whether his dozen are among the 16 confirmed by the newspapers. It also is not known if Higi is counting any deceased priests: the newspapers' numbers include three.

In such troubled dioceses, say experts, bishops must take the lead in providing clear direction to priests struggling to stay true to their pledge of celibacy.

One man charged with setting an example in the Lafayette Diocese is Father Sell, who investigates accused priests. When asked whether he has led a celibate life — the same question put to other priests interviewed — he twice replied that he has "tried." He never was more definitive.

Sell says it is a struggle to stay celibate. In explaining that, he echoed Higi's comment about the human condition.

"I mean (it's) the time in which we live," he says. "The society ... hedonism is the thing. Seize the day. Give in to all your pleasures."

No one is without sin, Higi reminded the faithful in November.

Concerned about the newspapers' investigation, the bishop issued a lengthy statement to Catholics of north-central Indiana.

In a special supplement to the diocesan newspaper, The Catholic Moment, Higi compared his dozen accused priests to Jesus' 12 disciples. He said two of those men were troubled, too. Judas, he pointed out, never was rehabilitated, but Peter was.

Comparing abusing priests to the apostles outraged a victim who read Higi's missive. Said Sego victim Schrader: "That's hypocrisy at its highest level."

In his article, Higi also said he regretted talking to the newspapers. He said he gave an interview and then answered written questions. What he did not say is that many of his written answers were scolding and nonresponsive. He repeatedly dismissed questions as "irrelevant" or "audacious."

Higi, who in his interview pledged to hold more public meetings alerting parishioners to accused priests, now said he saw little purpose in "inviting the public to sit as judge and jury" over abuse cases.

Yet, for a wrong to be forgiven, it must be admitted — on that point victims are clear.

At a prayer service in Rensselaer last fall for victims of sexual abuse and domestic violence, Higi acknowledged that some priests commit sexual abuse. Addressing all abuse victims, he said, "I need to tell you how very sorry I am." He urged anyone who needed help to step forward and accept counseling.

Still, Higi's words ring hollow for some survivors of abuse who long for a consoling touch or word from a bishop they view as distant and cautious.

The parents of a young man victimized years earlier by Father Bohlinger left one prayer service more hurt than before.

After the ceremony, the mother told Higi she wished her son could have attended. She recalls Higi's reply: "I thought we had taken care of all that."

The memory disturbs her.

"My son. All that."

"I wanted to kill the guy."

To that mother, the bishop seems fearful of coming too close to the suffering. "He chooses blindness," she says.

Blindness to victims' pain, adds Angela Mitchell.

Bishop Higi, she says, has never taken a moment to check on her. And all the late Bishop Gallagher ever wanted was to keep her family quiet, she says.

Scandal was long avoided. Church coffers were safeguarded. And her confessed abuser, Sego, was safely retired.

Forgotten were the needs of a hurt little girl who never outgrew the pain.

Says Mitchell: "I think they should have seen about me."

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.