First of Three Parts

By Bob Ehlert

Star Tribune

December 11, 1988

[See also Part Two and Part Three. These articles were scanned by BishopAccountability.org from a copy of the original newspapers.]

"Bless me, Father, for I have sinned."

Young Gregory John Riedle whispered those words through the fabric divider in the confessional at St. Thomas Aquinas Church in St. Paul Park.

"It has been a long time since my last confession," said Greg, who was 14 then, in 1978. "I swore at my little brother, at my mom and dad.... I am sorry for these and all of my sins."

|

But there was one sin, at least he thought it might be a sin, that he was told never to confess to anyone. Under any circumstances.

Not even to a priest.

So, time after time, Greg did not tell.

He listened to the priest's response. He made a mental note of his penance—a couple of Hail Marys and Our Fathers—and he received the priest's absolution and blessing.

Sometimes, just before he left, he heard the priest say, "And have a good day, Greg."

Sure enough, that would mean it was Father Tom. Father Thomas Paul Adamson.

It was Father Tom who taught Greg the sin that he was not to mention—if it even was a sin.

So through those years, 1977 to 1979, whenever he would go to confession, "even to Father Tom Adamson, that would never come up.... Never," said Greg.

The psychological demands of the secret sin began to pile up in Greg's conscience shortly after he became an altar boy at his church.

John and Janet Riedle, his parents, had encouraged their son to participate in the program, in which boys assist priests in church rituals. It was a good match because back in the summer of 1977 Greg had few friends and many idle hours to fill.

"I was a loner. Dad was working two jobs at the time. If I remember

right, there just wasn't time," said Greg, now 24, whose tall, slim

frame and styled blond hair make him appear much younger.

As an altar boy, Greg had a sense of belonging, contributing.

"I served mass almost every Sunday. I loved doing it," once he got over his initial nervousness, he said. "I loved shaking the little bells and moving the missal."

Janet Riedle was proud of her son's involvement and pleased with the relationship he had developed with Father Tom, the new priest in the parish.

Father Tom, who was 43 then, was a handsome, athletic and charming man. His reputation as a moderator of Marriage Encounters was blossoming in the Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis. His administrative skills had been praised by none other than Archbishop John Roach.

But what appealed to many of the parents of the parishes he served in was his willingness to minister to the youth. Father Tom seemed really to care for them. He spent time with them.

As soon as he arrived at St. Thomas Aquinas in 1976 he assumed charge of the training and recreation of the altar boys. It was in that setting he came to know Greg.

"It was just priest/altar boy," said Greg. "And then I heard about the outings that they had, and Father Tom was in charge of the outings. They'd go play racquetball, basketball, stuff like that."

In 1977, when Greg was 13, he started to go along with the group. During an outing to the swimming pool at the St. Paul Seminary Father Tom began to notice Greg Riedle.

Eventually, noticing Greg gave way to a sexual relationship between the priest and the boy that went on for two years, the priest testified. In February of 1987 the Riedles went public with a lawsuit against Father Adamson and the Catholic diocese that employed him. An out-of-court settlement was reached this past March. Greg Riedle and his mother speak freely of Father Tom these days, but the priest would not grant interviews for this story. His words and those of many other church officials are a matter of public record and were taken as a part of the lawsuit brought against Father Tom, the Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis and the Diocese of Winona (Minn.).

The events leading up to the settlement caused bishops to change passive policies into aggressive action against those who breach the sacred trust of their calling. The new policies, Catholic leaders hope, will prevent something like this from ever happening again.

But nothing can change the pain of all the parties because, as Archbishop Roach once wrote, this was a tragedy.

*

In the summer of 1977, on one of the recreational outings, Father Tom struck up a conversation with Greg Riedle and began to single him out.

"What I remember is (Greg's) aloneness, I guess, with the group—from the group," Adamson testified during one of his lengthy depositions.

As the summer progressed, the outings became a little more frequent and exclusive. Greg became Father Tom's favorite and the boy looked forward to spending time with the priest.

About every other weekend, it seemed, Father Tom would call and invite Greg on an outing. On many occasions the priest would pick Greg up at the Riedle house and make small talk with his parents.

|

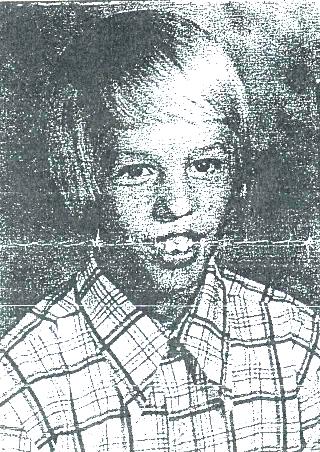

| Greg Riedle, when he was 9 years old. Four years later, in 1977, he became an altar boy and, shortly after, a victim of sexual abuse. |

"Once we got to know each other, they were happy that he was doing this, that he was going along, that he enjoyed it, those kinds of things," Father Tom said.

One Sunday, after Father Tom offered mass with Greg serving as altar boy, the two went on one of their routine outings. This time they were alone.

"We had just gotten done playing some basketball, and we were at a steam room at a YMCA in St. Paul," Greg said.

It is a small room, about 10 feet by 10 feet, where the windows often

are fogged. From the outside one

cannot distinguish human forms, and certainly not faces.

The priest reached for Greg's genitals and then whispered words that Greg could not believe.

Father Tom asked Greg if he ever played with himself, Greg said.

No, said Greg.

The priest asked the boy if he liked it, Greg said.

"I was scared; I still didn't know, all through it. There was something in me that said this isn't right. But at the same time there was part of me that said this feels good. It doesn't feel right; it feels right," Greg said. "It was like, you just trust him. There was no question about that. He was an authority figure that you look up to and trust. Not like a parent. That's how I felt. Someone I looked up to, someone I trusted. I had no reason, at the time, not to."

Later that day, the priest gave a warning that Greg would abide by for the next seven years.

"Don't tell anybody," Greg remembers Father Tom saying. "You'll get in trouble, and so will I."

*

Father Tom began to make his sexual rendezvous with Greg a routine. During the next several months they would meet and have sex in the basement of St. Thomas Aquinas church, the rectory, gas-station restrooms, motel and country-club saunas and pools, back to the steam room at the YMCA. Sometimes even in Father Tom's car, Greg testified in his deposition.

"Whenever he got the urge. Convenient locations."

One of the most convenient locations was a little room in the church basement. On at least one occasion, Greg said, Father Tom wanted and got sex right after the last mass on Sunday.

"He told me to go in the little room in the basement. He went and got his little duffel bag, he had his little massage (vibrator) thing and used it," Greg said. The other items in the bag Greg remembers included petroleum jelly and towels.

As the outings with Father Tom continued, gradually Greg became a willing participant.

"I looked forward to it for a couple of reasons. One, I enjoyed the recreation," said Greg, referring to the sporting activities. "... and I also knew every time I got together with him I was going to have an orgasm. Yes, it made everything else OK."

Much later Greg began to realize that Father Tom never wore his religious collar on the days that they would engage in sex. If that was a sign of the internal struggle the priest faced, then so were these words in his deposition:

"All my life I tried to be celibate," Father Tom said. "I mean, these things would happen, you see, they would happen, and there would be counseling or whatever, and I might go many, many months without any sexual outlet, masturbation or whatever."

*

Janet Riedle did not have the vaguest notion that Father Tom had recruited her teenage son for sex.

By that time the level of trust she had with her priests and her church could not be measured. It was infinite. Janet was a devoted parishioner who cleaned the church, who helped teach or baby-sit for women who taught religion classes.

She had counseled with a parish priest earlier in her life when she could not conceive. That led to the subsequent adoption of Greg through an agency of the archdiocese in 1964.

"I thought, hurray! Greg had a multitude of birthmarks, but that didn't bother us," Janet said. "You don't get guarantees when you have your own."

Whenever there was a need Janet thought of the church as an extension of her family. It was natural for her to turn to her church when she noticed some troubling things about her son.

After finding a file of photos of lingerie models that Greg kept she approached a family counselor, one recommended by her church. Although the counselor told her the pictures weren't a problem, she still worried.

"His school changed. His grades changed. His whole attitude changed. And at the same time we were counseling we were also confiding in Father Adamson," Janet said, her eyes beginning to well up with tears.

In 1978 the Riedles moved from St. Paul Park to Chisago City, Minn. When the family joined a new parish, St. Bridget of Sweden in nearby Undstrom, Minn., Greg wanted nothing to do with the altar boy program.

That bothered Janet some, but at least her son was still seeing Father Tom.

"He (Father Tom) would call on a Wednesday or something. He would

say, 'Can Greg come

back?'" Janet Riedle recalled. "We didn't think anything of

it, so we dropped him off at church, like maybe on a Friday evening. And

Father Adamson would drop him off at my grandma's ... on Sunday. So he

would actually be gone like for three days. And they would go golfing.

Or whatever."

Gradually, Greg became cool toward the priest's invitations to get together.

"Father Tom would call, leave a message, and Greg wouldn't answer it," Janet said. "And by then I had decided that was Greg's choice, and, if he didn't want to go, I couldn't do anything about that."

*

By the spring of 1979 the sex stopped. Greg had

tired of it. And besides, it had become increasingly

difficult for the two to meet. Greg was living at the north end of the

archdiocese and Father Tom was way to the south.

In June 1979 Father Tom, who had been an associate pastor at St. Thomas Aquinas, was placed in charge of Immaculate Conception Church in Columbia Heights.

While the priest's career was heading in a positive direction. Greg was getting into scrapes with his family, his school and the law. In 1980, at age 16, he was repeatedly running away from home and had begun to experiment with drugs. On the occasions when he was found he was sent to youth ranches and juvenile detention centers.

After one drug experience he ended up in the psychiatric ward at Mercy Medical Center in Coon Rapids. There, he began receiving therapy, including counseling sessions that involved his mother.

"They took me aside and asked me if John (her husband) had ever sexually abused any of his children. And I became angry and upset." Janet said.

No, he hadn't, she told the therapists.

But when she got home, she asked each of her other three children. In private, if their father had been abusing them.

"'You've got to be kidding,' they all said," recalled Janet. "None of this had happened.

"So I took Greg aside, and I explained to him that they (the therapists) want to know if anybody, a grandpa, uncle, anybody could have done this."

As always. Greg did not tell.

A psychiatrist told Janet that he knew Greg was keeping something to himself. "You know," Janet remembers the psychiatrist saying, "you can counsel until hell freezes over, and it's not going to make any difference...."

Unless Greg wanted to talk and let it out. But he could not.

It was as if the old warning was still in effect: "You'll get in trouble, and so will I."

*

Just a 17-year-old in 1981, Greg knew girls, but he didn't date, even though he socialized with groups of boys and girls his age. He had been confused by his sexual experiences with Father Tom.

After Greg dropped out of high school in 1982 he was around the house a lot—and so were some neighbor children that his mother had begun to baby-sit.

One day, as Greg was coming out of the shower, one of the little girls was just coming home from school to the Riedle house.

With the 7-year-old girl as an audience, Greg began to masturbate. Before long, he had enlisted that girl and her 4-year-old old sister to play a "game."

One of the rules of the game was never to tell. Just as Greg had been told by Father Tom to keep their secret, he had instructed the girls to keep quiet.

His warning worked on at least three occasions the game was played. On the fourth, the younger sister told her parents. They told Janet, who was so shocked and revolted she nearly became ill.

Janet Riedle was a mother and a care giver for small children whose parents had entrusted her with some of the most important people in their lives. Her own son had betrayed that trust, and she did not hesitate to call the authorities.

"I didn't turn Greg in to the police, but I had to report Greg to the welfare authorities or to whomever, and that was turned in to the police," she said, still wondering if her son was angry with her for that action.

In turning Greg in, Janet's hope was that he would get into treatment. His feelings were secondary. Greg was nonchalant about it.

"Being turned in was like, well, I'm doing something else wrong," Greg said. "I got to get in trouble for this now. No big deal. On a scale of 1 to 10, what I had done wrong seemed like a 1 or 2. It was so natural for me to act out, sick as that may sound."

Janet Riedle did not try to hide what had happened.

"We didn't keep it a secret. I was a baby sitter. I went to all of the people who brought their kids to me and said, 'Hey, this has taken place in my house.' And they had the option to check with their children. And to find someone else to baby-sit."

Some of the families, with the obvious exception of the abused girls' parents, wanted Janet Riedle to continue baby-sitting. Greg's mother took it upon herself to try to make sure the incident would never occur again by virtually banning her son from the house when the kids were present.

"He would come home, change his clothes and leave. Find something to do," she said. "He was not allowed to stay in the house. I wouldn't allow it."

Greg, meanwhile, pleaded guilty to criminal sexual assault.

"My sentence was two weekends in jail and treatment," Greg said.

He was ordered by the court to participate in a program for sex offenders in Minneapolis.

A few months after committing his sex crime Greg began to wonder if his experience with Father Tom had been the right thing. He said he was just learning about homosexuality. He wondered if that's what he was, a homosexual.

His curiosity led him to seek out Father Tom.

For the first time in about three years, the two met in July 1982 at Rosedale Center in Roseville. From there they went to a YMCA, where they had a swim and sauna—this time, Greg said, without sex. Back at the mall they sat and talked for a moment in Father Tom's car.

And then, according to Greg—Father Tom has denied the accusation—the priest reached over and touched Greg's genitals.

Greg said he grabbed Father Tom and tried to hurt his wrist.

"No," he said. "I don't do that anymore."

*

By the end of 1982 Greg had reentered high school in Chisago City (later earning his diploma).

His classmates were aware of his sexual offense, and Janet Riedle remembers how hard it was for her son to continue. But he finished.

In 1983 Greg was an adult in the eyes of the law. He had moved out of the house and begun to live on the streets. Occasionally he would show up at home. She knew Greg was supposed to be participating in a therapy program, but she could not force him to go.

In the winter of 1983, Greg helped burglarize a Forest Lake liquor store.

"(We took) all the booze we could put in this Chevelle. I did it for the excitement. I did it to get away with it. I had bread bags over my feet. I had gloves on. My hair was all up under my hat. I was smart," Greg said.

But not smart enough. Greg was arrested and charged with the liquor store burglary.

He spent Christmas 1983 in the Chisago County jail. While there, he said, he was evangelized by a church group. Greg said he became a temporary follower.

Janet Riedle had heard about Greg's new faith. But that news had been mixed in with reports of Greg's continuing criminal activity.

"I had gotten to the point where I thought I'm going to have a son who eventually is going to be in prison for the rest of his life because he was just doing habitual things," Janet said.

Concerned about Greg, John and Janet Riedle got into a discussion with him on a February day in 1984.

"I remember sitting, and his dad was sitting, and we were trying to talk to him," Janet said.

Greg sat in an old orange chair and began to speak of his religious experience. Janet was upset. Still devout Catholics, she and John Riedle were wary of the new religion.

"Why don't you go see Father Tom?" was her suggestion to Greg.

She remembers Greg answering that he had "only two fathers in the world. Dad and God." And he added that he was "sick and tired of people referring to priests as fathers."

Greg, tears in his eyes, rose from the chair and started to pace around the room.

John Riedle got up and began to speak, but he was interrupted by Greg, who said. "Sit down. You're not going to like this. You're going to hate me. You're going to tell me to leave. You're never going to want me back. But I'm going to tell you something. That (expletive), do you know what he did to me?"

Slowly the words about Father Tom came out. For the first time since the first incident in 1977, Greg confessed the sin.

He told about the outings. About the days and the nights and the sex. About the saunas. About the guilt.

His parents were dumbfounded. John Riedle, a machinist by trade who Greg said rarely shows emotion, wept.

As ugly and unbelievable as Greg's tale sounded. John and Janet Riedle believed him.

The warning of the psychiatrist at Mercy Medical Center flashed before Janet. There was something Greg was keeping to himself. You can counsel until hell freezes over, and it's not going to make any difference.

Greg's parents felt responsible. They had encouraged Greg to get involved in the altar boy program, allowed him to go with Father Tom for the long weekends.

"I listened to him, and I believed everything he was saying. And I sat there thinking, 'I'm going to throw up.'" Janet recalled. "The only thing I could think to do was to call the pastor at St. Bridget's in Undstrom, Father Bill Whittier."

"I believe Greg." Janet told the priest after they recounted the story to him. "I believe everything he said."

Father Bill, who declined to be interviewed for this story, didn't seem to be taking sides in the matter, Janet said. He did not try to defend Father Tom, whom he did not know. Nor did he side completely with the Riedles. But he was supportive.

*

By March 1984 Greg had pleaded guilty to a probation-violation charge that came as a result of his sex crimes and the burglary. He was sentenced to 21 months and was jailed temporarily in Chisago County until arrangements were made for him to enter what was then known as the St. Cloud Reformatory. He reported to St. Cloud on May 22,1984.

While Greg was in prison, Father Tom was an associate pastor of the Church of the Risen Savior in Burnsville.

The idea that Father Tom was still in a position to abuse other boys troubled Janet Riedle. As always, in time of distress, she turned to her church. This time, though, other than emotional support from Father Bill, she said she did not receive the kind of help she felt she needed.

Father Bill referred Janet Riedle to a Father Kenneth Pierre, a priest and psychologist who used to run the Consultation Services Center—an agency of the Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis.

Part of Pierre's job was to provide psychological counseling for people in the ministry and, occasionally parishioners.

In the midst of several unsuccessful attempts to contact Pierre, Janet Riedle got a call from a vocational rehabilitation counselor at Greg's prison. Greg had opened up to the counselor, Paul Ringsmuth, and told him about the sexual abuse he had suffered at the hands of Father Tom.

Ringsmuth began to look into the matter. He knew Greg had victimized others with sexual abuse, but nowhere in his records had it been mentioned that Greg himself had been a victim.

"Something isn't right. Let me see what I can do." Ringsmuth told Janet, she said.

Pierre finally returned Janet Riedle's call. She said he took notes of the charges she made concerning Father Tom and recommended that she call the archdiocese and ask to talk to Bishop Robert Carlson.

|

| Archbishop John Roach, above, praised Father Tom Adamson for his administrative skills in 1976, early in his stay in the Twin Cities. By 1985 he had asked for Adamson's removal. |

Carlson was a high-level administrator in the archdiocese and a confidant of Archbishop John Roach, the most powerful cleric in the archdiocese.

"I thought that was kind of awkward because that's kind of intimidating, "Janet said. "Call the bishop? I'm not about to do that. How in the heck do I, as a parishioner, call the bishop and say. 'OK, bishop, and there's this priest, and I have this son, and ...' I honestly, even though I believed Greg, I didn't think the bishop would believe us."

Paul Ringsmuth was not intimidated. After first seeking advice from a priest in the St. Cloud Diocese, he did what Janet Riedle wouldn't do and got in touch with several clergy in the archdiocese. Among them were Father Pierre and Bishop Carlson.

Ringsmuth, at the request of Janet Riedle, asked archdiocese officials what exactly was known about Father Tom. If he had been in treatment. Just what was going on[.]

In a letter to Ringsmuth, Pierre wrote:

"My last contact with Father Adamson before Mrs. Riedle called was in February of 1981.... The treatment centered on his sexual behavior and was motivated by his own concern to deal with his problem and by the pressure he was receiving from church authorities to do so.

"Since February 1981 Father Adamson has seen Dr. Joseph Gendron, a Minneapolis psychiatrist and consultant to us here at the Consultation Services Center. Father Adamson has seen him on a quarterly basis for maintenance and preventative therapy. To my knowledge, Father Adamson has been able to manage his problem with the assistance of Dr. Gendron since terminating his therapy with me early in 1981...."

Janet Riedle went from being troubled to angry. Greg had told her of the time in 1982 at the shopping mall when he claimed Father Tom tried to fondle him for the last time. The priest denies the incident.

Ringsmuth asked her it she was satisfied that Father Tom was seeking treatment. And she said, "Well, no, because what you've said now is that Father Adamson was having contact with Greg at the same time he was in a treatment program. What does that say, except that he goes for treatment and still has contact?"

Eventually Bishop Carlson called Janet Riedle. Then Carlson contacted Father Tom and asked him to meet with the Riedles. Carlson also planned to meet with Greg's parents at the archdiocese chancery in St. Paul. A date was set.

But before the Riedles' meeting at the archdiocese, they had their talk with Father Tom. Janet Riedle chose a Perkins Restaurant on County Rd. E north of St. Paul for the meeting.

"It was just John and I and Father Adamson." she said.

Janet cannot remember what she ate or who paid the bill. But she does recall that, throughout the meeting, Father Tom "never admitted to us face to face that he had ever done anything to Greg."

Leaving the restaurant, Father Tom hugged Janet Riedle, and she says he whispered softly:

"Just you remember that I'm not a wealthy person."

"And at that point in time I decided to hell with you," she said.

When Father Tom hugged her, she said, "It made me sick. And when he said what he said, it made me angry. So from that point on I just decided that this man was not interested in Greg. That he was only interested in not getting hurt himself."

But then Janet thought of Father Tom's mother, a woman she had never met, but a woman she somehow knew.

"And I knew his mother was older, an older person, and I knew, I thought of his mother because I knew how all this was going to hurt."

Janet Riedle cried again when the hurt came to mind. She wanted to keep talking, but words failed her.

"I didn't think it would be this hard," she said.

Monday: The Riedles and their attorney learn about Father Tom Adamson's

past. [See the Monday article.]

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.